Gender is difficult to categorise. Masculinity and femininity balance on a spectrum that ranges from one extreme to another, which can create confusion and uncertainty. Yet there are dominant representations of both masculinity and femininity expressed through mediated sport. These popular representations, conveyed through the dominant narrative, construct a binary definition of gender. Women are expected to behave in a feminine manner and men are expected to act in a masculine manner.

The dominant representation of masculinity defines men as being powerful, vigorous, assertive and courageous. Male athletes who achieve great success embody the dominant and popular understanding of masculinity. Male heroes within sport are worshipped for possessing these masculine traits. The athletes chosen to represent and reaffirm the dominant masculine ideology are typically white, middle class and heterosexual.

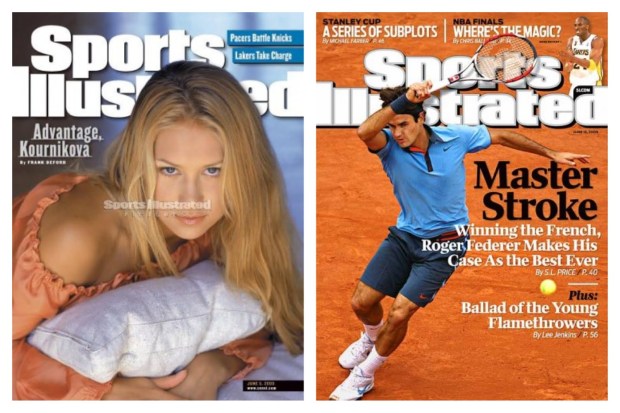

Femininity is defined in stark contrast to masculinity. A female sports person is “required to be both heroic – superior or exemplary in some way – and female – inferior by definition” (Thompson, 1997:397). Furthermore, female athletes are expected to express certain nurturing qualities which reaffirm the dominant narrative which portrays women as being protective, attentive, and tender, compassionate and unselfish. Female athletes who are chosen to represent hegemonic femininity are typically white, middle class and heterosexual.

Within both masculinity and femininity there are marginalised groups, who are excluded from the mainstream media and the popular narrative. These sub groups form a part of the individuals’ identity which is not fully accepted in society for a number of reasons. Additionally, these undesirable representations have been excluded from narrative and are perceived as ‘others’ and outsiders within society. As a result, these ‘others’ have been restricted in terms of participation, they have been misrepresented, deemed improper and stigmatized.

Stigmatized gender groups may include homosexuals, ethno religious identities, racial groups, class and people with a disability. Particular to men, stigmatized gender groups could also include “anti-sexist masculinities, men who don’t like sport, pacifist masculinities” (Whannel, 2002: 28). These marginalized groups are identified as being unalike and contrasting to the dominant gender ideology.

Modernized sport, which integrates standardised rules and specialisation, was created in Britain in the late 19th and early 20th century “by and for white, middle class men” in order to boast a dominant masculine ideology of innate primacy and supremacy, especially above women. Furthermore, sport has been used to instill the principles of hegemonic masculinity, whilst inflicting the stigmatized and marginalised sub groups to a silent existence. This dominance was, and continuous to be, a social construction.

At the present time, male sport is given precedence within the media, while female sport is given less attention. The disproportional media coverage manufactures a distinct divide between what women and men should and should not do. Importantly, the media appears to control and preserve the dominant masculine ideology by influencing the types of sport that each gender participates in.

The type of sport men and women participate in is important. It is important because each sport requires different bodily movements and different roles and responsibilities. Therefore to construct a popular narrative that describes gymnastics as a girl’s sport, would suggest that female athletes are better suited to individual sports that are elegant, technical, avoid contact and are aesthetically pleasing. Consequently this narrative, as well as encouraging women to participate, could deter men from taking part.

Mediated sport has constructed discriminatory and preferential coverage, which has resulted in a society dominated by patriarchy. The media, and the narratives it constructs, possesses the power to reaffirm the differences between masculinity and femininity within the realms of sport, moreover the media can belittle female athlete success and reaffirm hegemonic masculine ideology. The importance of this narrative is the construction of myth surrounding such sporting events and athletes, and the implications of these constructed symbols on gender identity. Narrative constructs an ideological discourse which seeks to either oppose or approve gender ideology. Fundamentally, the main purpose of mediated sport narrative is to nourish common and ill informed beliefs and identities relative to gender.

Narrative within mediated sport gives rise, predominantly, to a hegemonic masculine ideology that reinforces and re-imagines a society ruled by patriarchy. As a consequence of this constructed ideology gender differences and definitions of gender are difficult to locate. There is confusion within what it means to be masculine and what it means to be feminine, and importantly under what circumstances. What is known within this dominate imagined masculinity is that it is characterized within the media narrative as being white, heterosexual, aggressive and wealthy. Furthermore, it is perceived that masculinity is characterized in contrast to its significant other, femininity. Contrary to masculinity, femininity is characterized as being submissive and disproportionately delicate. Additionally within mediated sport female athletes are framed as sexual objects. Importantly, both gender ideologies display an explicit stance against homosexuality. It is almost forbidden within all media narrative. Furthermore, racial identities are restricted within the narrative upon the basis of the athlete being both successful and capable of financial gain. These assumptions created by the media narrative construct gender as a binary configuration, whereby an individual is either masculine or feminine. This is not the case. Especially while it remains unclear as to the definitions regarding both genders. What should be noted is that this is done within mediated sport in the most subtle of forms. The narrative is merely a product, and a re-submission, reproduced over time that constructs presumptions and imagined gender ideologies which lend to a chosen hegemonic power.

Reference List

Hargreaves, J. (2000) Heroines of Sport: the Politics of difference and identity. London, Routledge

Boyle, E. (2014). ‘Requiem for a “Tough guy”: Representing Hockey Labor, Violence and Masculinity in Goon’, Sociology of Sport Journal, Vol. 31, No. 3, pp. 327-348.

Scraton, S. & Flintoff, A. (2002) Gender and Sport: a reader. London, Routledge

Whannel, G. (2002) Media Sports Stars: Masculinities and Moralities. London, Routledge

Kennedy, E. and Hills, L. (2009) Sport, Media and Society. Oxford: Berg

Archetti, E. (1999) Masculinities: Football, Polo and the Tango in Argentina. Oxford, Berg

Allain, K. A. (2011). ‘Kid Crosby or Golden Boy: Sidney Crosby, Canadian national identity, and the policing of hockey masculinity’, International Review for the Sociology of Sport, Vol. 46, No. 1, pp. 3 – 22.

Atencio, M. Beal, B. and Yochim, E. C. (2013). “It Ain’t Just Black kids and white Kids”: The Representation and Reproduction of Authentic “Skurban” Masculinities’. Sociology of Sport Journal, Vol. 30, No. 2, pp. 153-172.

Boyle, E. (2014). ‘Requiem for a “Tough guy”: Representing Hockey Labor, Violence and Masculinity in Goon’, Sociology of Sport Journal, Vol. 31, No. 3, pp. 327-348.

Cooky, C. Dycus, R. and Dworkin, S. L. (2013). “What makes a woman a woman?” Versus “Our first lady of sport”: A comparative analysis of the United States and the South African Media Coverage of Caster Semenya’, Journal of Sport & Social Issues, Vol. 37, No. 1, pp. 31-56.

Ho, M. H. S. (2014). ‘Is Nadeshiko Japan “Feminine?” Manufacturing Sport Celebrity and National Identity on Japanese Morning Television’, Journal of Sport and Social Issues, Vol. 38, No. 2, pp. 164-183.

Khomutova, A. and Channon, A. (2015). ‘Legends’ in ‘Lingerie’: Sexuality and Athleticism in the 2013 Legends Football League US Season’, Sociology of Sport Journal, Vol. 32, No.2, pp. 161-182.

McDonald, M. G. and Birrell, S. (1999). ‘Reading Sport Critically: A Methodology for Interrogating Power’, Sociology of Sport Journal, Vol. 16, No. 4, pp. 283-300.

Mwaniki, M. F. (2012). ‘Reading the career of a Kenyan runner: The case of Tegla Loroupe’. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, Vol. 47, No. 4, pp. 446-460.